The Lewis Henry Morgan Collection of Mid-Nineteenth Century Iroquois Objects

- Native American Ethnography

The Lewis Henry Morgan Collection of mid-nineteenth century Iroquois materials was made by Morgan between 1849 and 1850 for the Historical and Antiquarian Collection of the New York State Cabinet of Natural History, which was to become the New York State Museum (NYSM). Morgan, now often described as "The Father of American Anthropology," collected or had made approximately 500 objects, representing all aspects of Iroquois life. In this, he was aided by members of the Seneca Iroquois William Parker family, particularly son Ely S. Parker, who is best known as aide-de-camp to General Ulysses S. Grant during the Civil War. Morgan's 1848, 1849, and 1850 reports, detailing the traditional production and use of these objects, were pathbreaking ethnographic documents. Tragically, a 1911 fire in the State Capitol destroyed much of the collection, making the remaining pieces particularly rare and significant.

In 2000, the NYSM received a matching grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to provide conservation treatment for the eleven most fragile objects remaining in the Morgan Collection, to produce custom-made supports for the remainder, and to help acquire new storage cabinets for the collection. All objects were photographed, and the Museum's database was updated with complete descriptive and background information for each piece. Also in 2000, the Museum acquired, through the generous donation of Mr. William Guthman, a set of watercolors painted in 1849 that depict 35 of the objects collected in that year.

History of the Lewis Henry Morgan Collection

-

About Lewis Henry Morgan

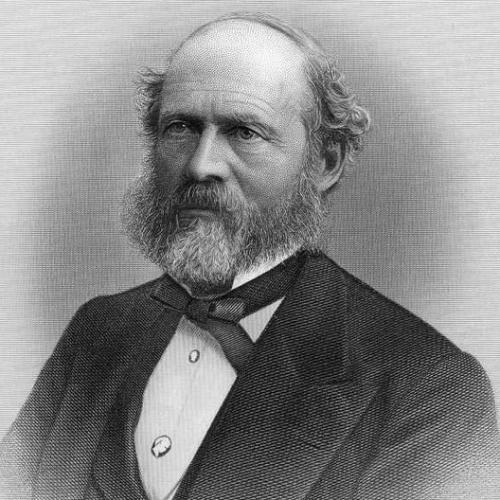

Lewis Henry Morgan was born in 1818 near Aurora, Cayuga County, New York, the ninth of 13 children. After graduating from Aurora Academy and Union College in Schenectady, and being admitted to the Bar, he moved to Rochester in 1844 to practice law.

As a young man, Morgan belonged to a fraternal society that came to be called the Grand Order of the Iroquois, leading its members in research on Iroquois history and culture. He interviewed Iroquois elders and visited the Seneca Iroquois Tonawanda reservation, located between Buffalo and Rochester, to witness a council held there. In 1845, the Order offered support to the Senecas in a fight to retain their Tonawanda reservation, an effort in which Morgan was involved. In 1846, Morgan published the fruits of his early research in The American Review as a series of "Letters on the Iroquois." That same year saw his adoption into the Seneca Hawk Clan as Ta-ya-da-o-kuh ("One Lying Across," or "Bridge"). Morgan's early work among the Iroquois, including excerpts from his journals, is detailed in Elisabeth Tooker's Lewis H. Morgan on Iroquois Material Culture (1994).

He married Mary Elizabeth Steele in 1851, started a family, and during the 1860s served in the New York State Assembly and Senate. Until his death in 1881, Morgan made Rochester his home. Throughout his life, Morgan maintained an intense interest in Native American lifeways and social organization. His research and theoretical contributions eventually earned him a prominent position in the emerging new field of anthropology. Between 1851 and 1881, he published a series of influential books and, in 1879, he was elected President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

-

Lewis Henry Morgan and the New York State Museum

The New York State Cabinet of Natural History was established in 1843 to house the collections gathered from the 1836-1841 geological and natural history survey. In 1847, it was expanded to include a historical and antiquarian collection, for which contributions and suggestions from the public were sought. In a circular, fellow citizens were asked for "their aid, in furnishing the relics of the ancient masters of the soil, and the monuments and remembrances of our colonial and revolutionary history."

One of the people who answered their call was Lewis H. Morgan, a young lawyer from Rochester. In 1848 and 1849, he donated archaeological and ethnographic specimens that he had collected, and maps of five archaeological sites. He strongly encouraged the project, suggesting names of other collectors who might be induced to donate their collections and offering his help in furthering the project.

Morgan proposed to acquire for the Cabinet a collection of the complete range of objects being made and used by members of Indian tribes within New York. The regents accepted his offer, and in 1849 placed $215 at his disposal for this purpose. In 1850, an additional $250 was allotted.

(By the mid-nineteenth century, most Native Americans remaining in upstate New York were members of Iroquois groups. Prehistorically, these tribes had occupied the central part of the state. Five groups -- west to east, the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk-- formed the League of the Iroquois probably during the early Contact Period. In the eighteenth century, the Tuscarora were admitted. By Morgan's day, their land holdings in the state had been cut to a scattering of small reserves.)

-

The William Parker Family

Morgan's research on the Iroquois and collecting of Iroquois objects for the State Cabinet of Natural History were carried out with the essential aid of members of the Parker family of Tonawanda. The collaboration and long-term friendship began in 1844, with a chance meeting between Morgan and 16-year-old Ely S. Parker at a bookstore in Albany.

William Parker and his family, while prominent in Tonawanda Seneca affairs, were unusual for their day in regard to the extent of their participation in the world outside the reservation. After serving in the War of 1812 in a large company of Iroquois allied with the Americans, William returned home to marry Elizabeth, a niece of the Seneca chief and religious leader, Jemmy Johnson (Sose-há-wä), grandson (in Seneca kinship terminology) of the prophet Handsome Lake.

All six of William and Elizabeth's children who survived to adulthood were educated at Baptist missionary schools, learning English at a time when most Senecas spoke only Iroquois languages. Because of his facility with English, young Ely was pressed into service as a translator, travelling with delegations of chiefs to Albany and to Washington, D. C., during their efforts to retain control of Tonawanda reservation lands. It was during one of these trips that he and Morgan first met. Through Ely, Morgan was able to interview Johnson and other prominent Seneca leaders, and to intensify his study of Iroquois life.

Morgan was instrumental in Ely's enrollment at Aurora Academy, Morgan's own alma mater. Ely went on to study first law and then engineering, overseeing a wide variety of construction projects and later becoming a U.S. Army Captain of engineers. In 1851, this remarkable young man was named Grand Sachem of the Six Nations. Among many notable accomplishments, he served in the Civil War as aide-de-camp to General Ulysses S. Grant. Afterward, under President Grant, he became the first Native American Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (1869-1871).

Ely's younger sister and brother, Caroline and Newton, were among the first recipients of scholarships established by the New York State Legislature, at Morgan's behest, to allow Native Americans to attend the state normal school at Albany. Their older brother Nicholson also studied there.

Daguerreotypes (and images derived from them) of William, Elizabeth, and five of their children are included in Elisabeth Tooker's Lewis H. Morgan on Iroquois Material Culture (pp. 64-71). In some of them, Levi, Caroline, and Newton Parker are shown wearing garments and carry objects from Morgan's collections for the New York State Cabinet of Natural History, underscoring their involvement in gathering these materials.

-

Morgan's Collection for the State

The collection that Morgan and the Parkers brought together for the State contained approximately 500 items, including both utilitarian and ceremonial objects. Some were well-used, purchased from their owners. Others were specially commissioned for the collection.

The range of objects was developed through consultation with the Parkers, and many were produced by family members. For example, Caroline, a notable needlewoman, made many of the elaborately beaded garments and bags. (More information about her can be found at the NYSM Women's History web site; see Further Information.) The house model was William's work. Elizabeth, a basket maker, no doubt contributed significantly to the collection. Most items came from Senecas at Tonawanda, but Morgan also collected at the Six Nations reserve on the Grand River in southastern Ontario, where people from all six of the Iroquois nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora) resided.

The Parkers also furnished Seneca names for the objects they made and obtained, as well as information about their production and use.

Items collected included traditional raw materials, foodstuffs, tools, containers, and some ceremonial objects. Garments and ornaments were those being worn at the time, and tools and containers were of types still in use. Included were both ordinary, everyday, utilitarian objects and more highly decorated items serving similar functions. Plain moccasins and quilled moccasins, carved wooden ladles and expediently made ladles of folded bark, decorated and undecorated burden straps all were there. Some items, such as beaded purses and pin cushions, were designed primarily for sale to non-Iroquois customers; fancy beadwork was an important source of income for many Iroquois women and their families.

The collections that Morgan made for the State in 1849 and 1850 were valuable in and of themselves, but their value was enhanced tremendously by the reports about them that he prepared for the Regents. In these, he provided carefully detailed illustrations of each type of object (see Illustrations from Morgan's Reports to the Regents) collected, and extensive information about how each one was made and used. These documents are among the earliest anthropologically-oriented comprehensive descriptions of material culture.

Morgan's 1851 book, League of the Ho-de'-no-sau-nee or Iroquois, which described Iroquois lifeways, material culture, and social organization, included much information gained during his collecting activities for the State. In fact, most of the illustrations from the Regents Reports were included in this larger publication.

Morgan's introductory sentences to Book III of the League speak eloquently to the key role of material culture in understanding a people's way of life, and thus to the importance of collections such as the ones he had made for the State:

"The fabrics of a people unlock their social history. They speak a language which is silent, but yet more eloquent than the written page. As memorials of former times they communicate directly with the beholder, opening the unwritten history of the period they represent, and clothing it with perpetual freshness."

Morgan acknowledged his debt to the Parkers, especially Ely, who served as translator, guide, and colleague over the course of this project. This was spelled out in his dedication to the League publication: "To HAU-SA-NO-AN'-DA (Ely S. Parker) A Seneca Indian, This Work, the materials of which are the fruit of our joint researches, Is Inscribed: in acknowledgment of the obligations, and in testimony of the friendhip of THE AUTHOR."

-

Use of the Collection, 1850-1910

Over the years, the primary use of objects in the Morgan Collection has been for exhibit. They also have figured prominently in research, appeared in a variety of publications, and contributed to other educational endeavors. Because of their relative antiquity and the large range of activities they embodied, these items became the workhorses of the Museum's collections.

These uses are exemplified in the work of Arthur C. Parker, a great-grandson of William Parker. A. C. Parker served as Curator of Archaeology and Ethnology at the New York State Museum between 1905 and 1925. He came to the job after working as an archaeologist for the American Museum of Natural History and the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, and left it to become Director of the Rochester Municipal Museum (now the Rochester Museum and Science Center). One of his well-known works is a biography of his granduncle Ely.

In his ethnographic research, Parker followed in the footsteps of Morgan, collecting a wide range of Iroquois objects and documenting them extensively. Because he had used or observed many of them as a child and could learn more about them with no need for a Seneca interpreter, his understanding of their place in Iroquois life was comprehensive and detailed. According to Iroquois ethnographer and former NYSM Director William Fenton, in at least some of his work, Parker "out-Morganed Morgan." That is, Parker researched and produced monographs, most notably Iroquois Uses of Maize and Other Food Plants (1910), along the lines of Morgan's reports to the Regents, but far more comprensive. In them, he (like numerous other researchers before and since) utilized objects from the Morgan Collection in a variety of ways. Both photographs and engravings of them appear in his publications, as examples of object types. In addition, Parker took them out into the field, producing posed photographs of Seneca Iroquois people wearing and using items from the NYSM collections including many collected by Morgan.

Parker was understandably proud of the ethnographic and archaeological objects under his care. In 1910, he put a large proportion of them on display in a series of splendid cabinets along the forth floor corridor of the New York State Capitol building. Incorporating over 1000 items gathered by Morgan, by donors such as Harriet Maxwell Converse, and by Parker himself, the ethnographic materials in this exhibit embodied a priceless heritage of well over sixty years of Iroquois material culture.

For a few months, an unparalleled group of objects was available to the public. Then came disaster.

-

The New York State Capitol Fire, 1911

On March 29, 1911, fire broke out in the Capitol. From the Assembly Library, it spread to the State Library near the museum displays. Flame, water, and breakage due to collapse of the sandstone ceiling brought almost total destruction to the collections on exhibit. Of 10,000 archaeological artifacts and ethnographic objects, only about 1500 were recovered, most of which were damaged. A mere 512 retained identifiable catalog numbers.

Approximately 50 of the Morgan Collection items fortunately had been removed to the curator's office for study before the fire. Most of the remaining 450 were damaged or destroyed. Even if not completely consumed by fire, many objects lost their identifying labels.

For many decades after the disaster, curators struggled to determine which of the remaining items had been part of the original Morgan Collection. A few had Morgan's own paper labels still affixed. Others, of unique design, could be identified from their images in Morgan's reports to the Regents, or, in a few instances, from written descriptions.

Even now, uncertainty remains. Of over 100 ethnographic and archaeological items listed in the NYSM collections database in 1999 as collected by Morgan, no more than 57 have unimpeachable pedigrees. Conversely, objects from the Morgan Collection, but unidentified as such, may well still be present within the Museum's larger collections.

Many items in the collection, from a bark canoe to a burden frame to a unique grass shoulder ornament to a skirt described by Morgan as "the finest specimen of Indian beadwork ever exhibited" are now known only from illustrations in his reports. Many more, such as an "eye showerer," a "finger catcher," a bearskin bag, and a large number of special-function baskets, were not illustrated and were described only minimally, so are difficult or impossible to visualize today.

-

Use of the Collection, 1911-2001

After the fire, remaining objects from the Morgan Collection continued to see heavy use for exhibition, education, and research. Because they were among the oldest and rarest items in the Museum, they were much in demand.

First and foremost, they were called upon to populate exhibits and displays in the "New Museum" located in the magnificent State Education Building on Washington Avenue. The initial exhibits, which opened in 1916, included six life-sized dioramas or "life groups" showing important aspects of traditional Iroquois life, as well as ethnographic objects and archaeological artifacts arranged in display cases. Sadly, in many instances the display conditions were not ideal for preservation of the objects.

Several Morgan Collection objects, including a cradleboard and at least one rattle, were utilized within the dioramas, which for almost 60 years were among the most popular displays at the Museum. For the most part, this provided a benign environment for these items, although it is possible that some of the exhibits may have been treated with toxic pesticides over the years.

Unfortunately, the gleaming new display cabinets for the majority of the ethnographic items, including those from the Morgan Collection, were located under a large skylight. A number of the textile items suffered extreme light damage -- fading and deterioration of fabric -- under these conditions. Later displays, while shielded from sunlight, were mounted under continuous artificial light that also held the potential for damage.

In 1973, when the New York State Museum again moved to new quarters in the Empire State Plaza Cultural Education Center, fewer objects from the Morgan Collection were part of the permanent exhibits. Nevertheless, Caroline Parker's beaded skirt was on display there for almost a decade, until it was removed for conservation treatment in 2000.

Over the past century, items from the Morgan Collection frequently have participated in short-term exhibitions at other institutions. For instance, a beaded and quilled hair ornament (NYSM 36780(link is external)) recently was included in an exhibit on Iroquois beadwork organized by the McCord Museum of Montreal, which is travelling to four other museums in Canada and the United States.

During the 1970s and 1980s, several large groups of Iroquois objects, including a number from the Morgan Collection, were provided on long-term loan to Native American museums that at the time lacked large collections of their own. These include the Akwesasne Museum (Hogansburg, New York), the North American Indian Travelling College (Cornwall Island, Ontario), the Seneca-Iroquois National Museum (Salamanca, New York), and the Woodland Cultural Centre (Brantford, Ontario). Thus, the heritage of ingenuity, craftsmanship, and style represented by these fine objects was made available to a much wider audience than visitors to the State Museum. The oldest items, including most of those collected by Morgan, now have been returned to Albany, to provide better conditions for their care and preservation.

Besides the informational value of the exhibits in which they have been displayed, Morgan Collection objects have participated in a wide variety of other education-oriented projects. A number of them were replicated for inclusion in educational kits about Iroquois life that were loaned to schools for classroom use. Their images are frequently used in slide talks by Museum staff and others, and have been included in countless textbooks and art history volumes over the years.

The collection is particularly valuable now for study and research, allowing people of the twenty-first century to learn how nineteenth-century Iroquois people made and used a wide variety of objects essential to their everyday life.

Year after year, the Morgan Collection continues to attract researchers and appreciators. Academic anthropologists and historians, artists, historical reenactors, contemporary craftspeople (particularly beadworkers), Native Americans, school children, and Regents of the University all have ventured into Museum storage to study, or simply to view, these tangible connections to an earlier way of life and to the people who lived it 150 years ago.

-

Conservation and Rehousing Project

By the end of the twentieth century, it was apparent that a number of the remaining Morgan Collection objects were in need of conservation treatment. Textile items from the collection - subject to light damage, insect damage, and stress from hanging - were particularly fragile. Some of the bark and wood objects also had been damaged over the years.

The NYSM sought and received a matching grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to provide conservation treatment for eleven of the most at-risk objects, to construct special supports for all objects in the collection, and to purchase high-quality storage cabinets for the collection. The project also included black and white and color photography of all items in the collection to minimize the need for future handling.

During 2000, consulting conservator Gwen Spicer treated nine garments (or sets of garments), a basket, and a bark quail trap. She painstakingly removed dirt, stabilized loose parts, and provided custom-made padding, supports, and containers. Images of them before and after treatment show how urgent was the need for this work, and the details of what was done to stabilize their condition.

Museum technicians Robin Finch and Jim Walsh created new supports and containers for the remainder of the collection. These allow the objects to be moved from place to place and to be examined closely, without the need to handle them directly.

New high-quality storage cabinets were purchased to house the collection, constructed so as to buffer these important objects from deleterious environmental conditions. Included was a special-order cabinet large enough for garments to be laid flat rather than being folded to fit the much smaller drawers of standard cases.

-

Additional Collections of Iroquois Materials by Morgan

The New York State Museum's Morgan Collection has two counterparts curated elsewhere.

In 1860, Morgan made a collection of Seneca Iroquois objects for the Royal Museum of Copenhagen (now Danish National Museum). A descriptive list of these items and related correspondence with the museum's representative, W. Raasloff, is included in the Morgan Papers at the University of Rochester Library.

Morgan's own collection of ethnographic objects, including many of Iroquois origin, is now curated at the Rochester Museum and Science Center. It has been described in two articles by Richard Rose, as well as on the Rochester Museum's web site.

Join the Conversation

The New York State Museum is a program of the University of the State of New York

New York State Education Department

Museum Hours

Tuesday - Sunday, 9:30 AM - 5 PM

Closed all state-observed holidays

New York State Museum Cultural Education Center 222 Madison Avenue Albany, NY 12230