5. Queer Black Artists During the Harlem Renaissance

Exhibit Feature & Artifact:

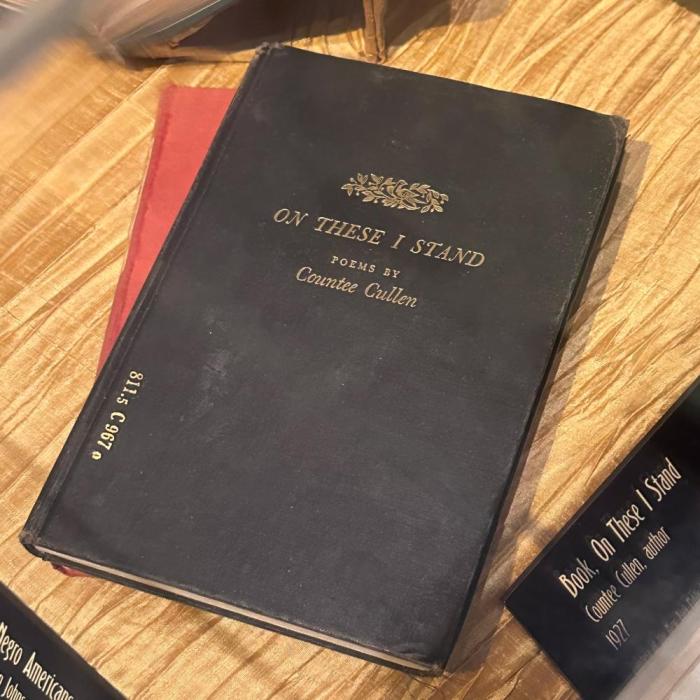

The Cotton Club exhibit feature | Book, On These I Stand, by Countee Cullen

Where to find them:

Harlem in the 1920s

As the arts and Black culture flourished in Harlem in the 1920s and 30s, so too did several queer Black artists and intellectuals. While many remained closeted publicly to appeal to mainstream audiences and norms of the time, they found some ability to express themselves and pursue same-sex relationships in Harlem.

Gladys Bently

One notable performer who did not remain closeted was Gladys Bently (1907–1960). Bently moved to Harlem from Philadelphia around 1925—she had written about being attracted to women and being comfortable in men’s clothing from a young age, and in Harlem, she would have found acceptance and a like-minded community. Harlem was also a haven for wealthy pleasure seekers during prohibition, and Bentley began performing as a drag king (typically a female performer who dresses in masculine drag) at “rent parties,” private parties with live performances. Popular during Prohibition, admission was charged to pay for rent money and alcohol. Bently moved on to performing in nightclubs after a successful audition at the Mad House and was known for her appearances at the Cotton Club and the Clam House.

Bently became known for her dapper masculine dress, her bawdy renditions of popular songs, and her deep growling voice. Of her clothes, she wrote, “For the customers of the club, one of the unique things about my act was the way I dressed…I wore immaculate full white dress shirts with stiff collars, small bow ties and shirts, oxfords, short Eton jackets and hair cut straight back.” She had a keen awareness of her public image and the power of shock value, often feeding tidbits of gossip to the press, including a story of her marriage to a white woman.

With the end of the Prohibition era and the decline of Harlem nightclubs, Bently moved to California. In the press, she began presenting as a “cured” woman, living under more traditional gender roles. In a 1952 article for Ebony, Bently wrote, “for many years, I lived in a personal hell…Like a great number of lost souls, I inhabited that half-shadow no man’s land which exists between the boundaries of the two sexes.” Scholars of Bently believe that the article, and her public façade at the time, likely reflected her continued awareness of the press, and the oppressive threats against homosexuality brought forward in the McCarthy era.

Countee Cullen

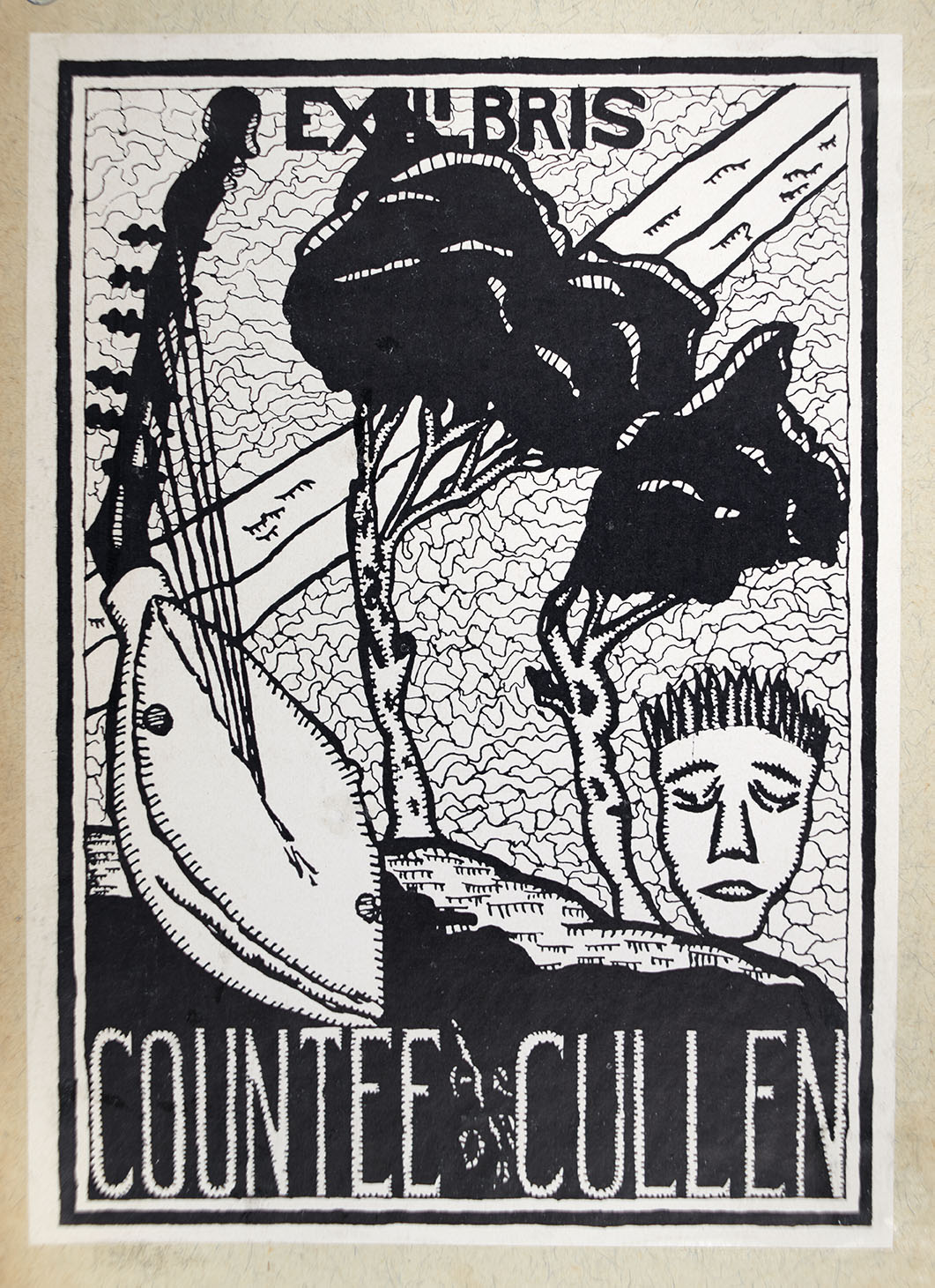

Also represented in this gallery is a book by prominent queer Black poet Countee Cullen (1903–1946). While he was friends with many openly gay writers, Cullen himself remained closeted and struggled to come to terms with his sexuality and the shame he felt with it. He had two brief marriages to women and also quietly dated men.  New Discovery: Countee Cullen’s Bookplate While not on display, the Museum recently found this bookplate in Cullen’s copy of Precis D’Explication Francaise: Methode et applications (Precise Analysis of French: Methods and Applications). The imagery may relate to the Greek myth of Orpheus, a musician, poet, and prophet.

New Discovery: Countee Cullen’s Bookplate While not on display, the Museum recently found this bookplate in Cullen’s copy of Precis D’Explication Francaise: Methode et applications (Precise Analysis of French: Methods and Applications). The imagery may relate to the Greek myth of Orpheus, a musician, poet, and prophet.