Women of Science Spotlight: Mary Banning

Beyond "Polite Botany": The Legacy of Mary Banning and Women in Early Mycological Research

Mary Elizabeth Banning (1822–1903), a self-educated mycologist from rural America who spent decades studying fungi in Maryland, wrote, “Fungi are considered vegetable outcasts. Like beggars by the wayside dressed in gay attire, they ask for attention but claim none."

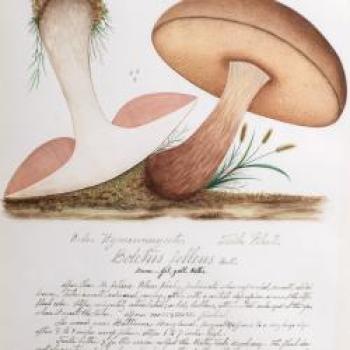

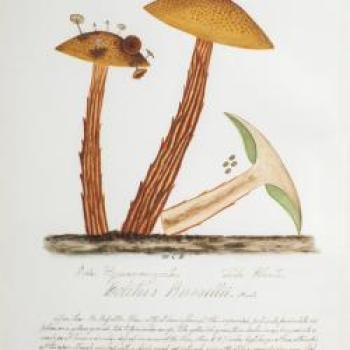

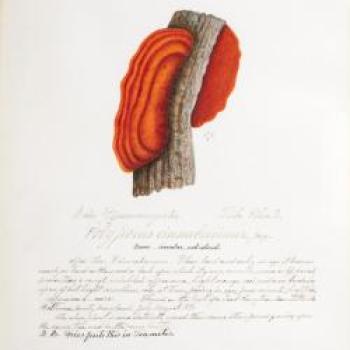

Banning was a diligent and talented mycologist who studied mushrooms growing in Maryland in the mid-1800s. She corresponded frequently with the renowned mycologist, Charles H. Peck, who founded the fungal collection at the New York State Museum. Over her life, she described 23 species that were new to science and produced fantastic illustrations, notes, and narratives about her fungal encounters.

In 1889, Banning completed the unpublished manuscript, "The Fungi of Maryland," containing 175 exquisite watercolors and descriptions of species of mushrooms. Unfortunately, despite her pioneering work, Banning was near poverty towards the end of her life and died in obscurity. Her manuscript, which she entrusted to Charles Peck, also remained hidden for almost 100 years until it was rediscovered in the 1980s. Today, it is one of the most prized objects in the New York State Museum's collections.

Beyond "Polite Botany": The Legacy of Mary Banning and Women in Early Mycological Research

Professionalization of natural history research greatly expanded in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, a time in which women were systematically kept under-educated and excluded from formal participation. But fungi — commonly regarded by Western European “gentlemen” as inelegant, useless, gross, and deadly — were considered to be suitable study subjects for women. The lower taxa meant lower prestige and were therefore often relegated to the domain of women as the exploration of fungi and other lower taxa (such as lichens, algae, and mosses) was not considered a serious concern to the male institutions of higher learning. Some men, such as John Lindley (1799–1865), the first professor of botany at the University of London, distinguished between “polite botany,” which included fungi, was for the “amusement” of women, and “botanical science,” which was a serious discipline for men.

Historically, mycology was therefore unique among other organismal fields for having a greater number of notable women contributors, as well as women in positions of leadership in mycological societies. Some accomplished women in the field included Catharina Dörrien, Marie-Anne Libert, Élise-Caroline Bommer née Destrée, Mariette Rousseau née Hannon, Mary Elizabeth Banning, Beatrix Potter, and Annie Lorrain Smith — all self-taught mycologists who contributed substantially to research in the lead up to the 20th century. Barred from formal institutions of science, women in fungal taxonomy were often seen as “isolated eccentrics,” devoting the precious free time they had outside of domestic obligations to pursuing their true love: the science and natural history of misunderstood and maligned organisms.